An Introduction to Fluorescence (Part 1)

Written/Edited by Dr. Ryan Robinson, PhDIntroduction

Fluorescence is a property possessed by certain materials, known as fluorophores, by which these materials absorb short-wavelength incident radiation and emit longer-wavelength radiation. Fluorescence occurs when high-energy incident radiation is absorbed by a fluorophore, causing the material to enter a vibrationally and electronically excited state. Upon relaxation to the ground state, a lower-energy photon is emitted from the material. Materials may possess fluorescent properties by virtue of their atomic, molecular, or macro-molecular structure.

- A fluorophore absorbs high-energy incident radiation.

- The absorption of elevates the fluorophore to an unstable, electronically excited state.

- Electrons in the fluorophore return to the relaxed ground state, emitting a photon of longer wavelength.

The shift in wavelength between light from the excitation source and emitted light is due to loss of energy (mostly in the form of heat). Unless additional energy is introduced to the system from an external source, the emitted photon will always be lower energy (longer wavelength) than the excitation source. For example, GFP (Green Fluorescent Protein) is excited by short-wavelength blue light (λmax~488nm), and emits longer wavelength green light (λmax~519nm). This phenomenon is known as Stokes shift.

Fluorescence: at work in the life-sciences

Fluorescence has always played a role in the natural world. As a byproduct of their molecular composition numerous naturally occurring minerals will fluoresce in the visible spectrum when exposed to ultraviolet light. Certain species of marine animals like the jellyfish Aequorea victoria also produce fluorescent proteins that emit light in the visual spectrum. The stunning and magnificent visages produced by some of the more colorful forms of naturally occurring fluorescence have captivated countless generations of researchers and naturalists. Innovative biologists and biochemists have also developed a number of techniques that allow them to leverage this impressive phenomena and employ it as a tool in nearly every avenue biological research.

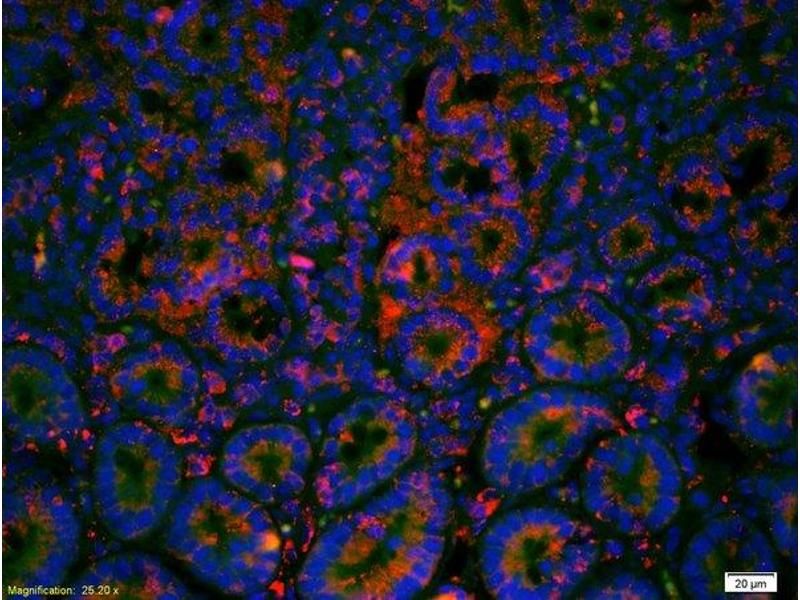

An IF micrograph demonstrating the distribution of Cadherin 1 in mouse intestinal tissue using antibody ABIN1387847 and a Cy3 tagged secondary antibody

Paraffin preserved mouse intestinal tissue has been labeled using two separate fluorescent dyes. The dye DAPI (blue), binds directly to DNA and is used to label the nucleus for a structural reference point within the cell. The dye Cy3 (red), is conjugated to an antibody which binds the glycoprotien Cadherin 1, demonstrating enrichment of this protein at the plasma membrane. The primary antibody used for this experiment was the independently validated product ABIN1387846.

The most recognizable technique utilizing fluorescence in the life-sciences today is microscopy. Cover articles in high impact journals are dominated by vibrant, full color micrographs displaying beautiful fluorescent in situ hybridizations or immunofluorescence labeled tissue sections. However, the use of fluorescent probes has also dramatically improved other, less colorful experimental techniques as well. Flow cytometry, western blotting, and DNA electrophoresis have all become simpler, faster, and more powerful through use of modern fluorescent labels.

Use of a fluorescent label can simplify and improve the western blot technique, reducing the number of steps necessary to carry out the experiment, and the amount of time required to complete it. It carries the added benefit of generating much less chemical waste than traditional chromogenic methods.

Fluorescent dyes and proteins

Today, fluorophores are commonly used to label biological materials in nearly every life-science discipline. Fluorophores used in the life-sciences commonly fall into one of three categories:

- Fluorescent Dyes: Small, organic fluorescent molecules, either natural or synthetic, that can be used to label biologically relevant molecules. (e.g. Fluorescein, DAPI, DiI, Ethidium Bromide, Cyanine & Alexa Fluor™ Dyes)

- Fluorescent Proteins: Larger, biologically produced proteins, either natural or synthetic, that fluoresce as a byproduct of their macromolecular structure. (e.g. GFP, RFP, YFP)

- Quantum Dots: Nanoscale synthetic fluorescent crystals with an incredibly diverse range of uses.

The three classes of fluorescent probes possess similar properties, and many fluorescent proteins have been engineered to share a nearly identical excitation and emission profile to commercially available dyes (e.g. mutations to green fluorescent protein produced eGFP which is almost spectrally identical to the dye FITC). However, they are often applied in different scenarios.

Fluorescent proteins like GFP or RFP are commonly used to label the protein product of a specific transgene. Using molecular cloning techniques the coding sequence for a fluorescent protein is coupled to the coding sequence for the researcher's protein of interest. The resulting "fusion-protein" is a combined unit containing both the researchers target and the fluorescent protein. This powerful technique allows a researcher the opportunity to track the sub-cellular distribution and movement of their protein of interest in vivo.

Featured RFP Antibodies

- (356)

- (11)

- (1)

- (16)

- (9)

Small fluorescent dyes, on the other hand, are most often used in in vitro experiments. Some dyes like DAPI, DiI, or Ethidium Bromide will associate with biologically relevant molecules or structures on their own, allowing them to be used independently to label these structures. Other dyes like Fluorescein, Cyanine, Rhodamine, or the wide variety of Alexa Fluor™ dyes are commonly used as conjugates for primary or secondary antibodies, which are used in immunolabeling experiments like:

- Immunofluorescence

- FACS/Flow Cytometry

- Western blotting

- and many others...

The GFP-booster provides a unique opportunity to compare signal generated between a modern fluorescent dye (ATTO488) and a fluorescent protein (GFP).

GFP-boosters are a novel type of intracellular antibody that allow a researcher to get the best of both worlds by labeling a GFP-tagged fusion protein with a brighter, more stable fluorescent dye, thereby enhancing and improving the signal generated.

In the image above, the dye (ATTO488) absorbs and emits light in a nearly identical manner to GFP, but provides a much brighter signal.

Quantum dots are the most recent introduction. While these unique, synthetic nanocrystals display exceptional promise in the life-science world, they have not yet gathered wide-scale acceptance and use on the same level as fluorescent dyes and proteins. Quantum dots will be discussed in more extensive detail in our upcoming article, advanced fluorescence techniques and tools.

Advancements in chemical synthesis and a consistent push for more flexible and efficient fluorophores have resulted in the development of hundreds of reactive fluorescent dyes that span the UV, visible, and infrared spectra. These dyes have often been chemically optimized for for specific applications, or for use with specific instrumentation.

While the development of new dyes and reagents has significantly expanded the role and flexibility of the fluorophore in life-science research, the sheer number of options often leaves a researcher perplexed as to which specific fluorophore is best suited for a given application. The matter can become particularly complex when choosing a fluorophore for a double-labeling experiment which requires the use of multiple compatible fluorescent molecules.

An Introduction to Fluorescence (Part 2) covers the specific intricacies of choosing a fluorophore for an experiment, including the most common criteria for consideration.

Offered pre- and post-sales consultation and support to antibodies-online customers. Provided troubleshooting and technical assistance with proteomics and genomics experiments. Composed and distributed cross-channel digital marketing campaigns.

Go to author page